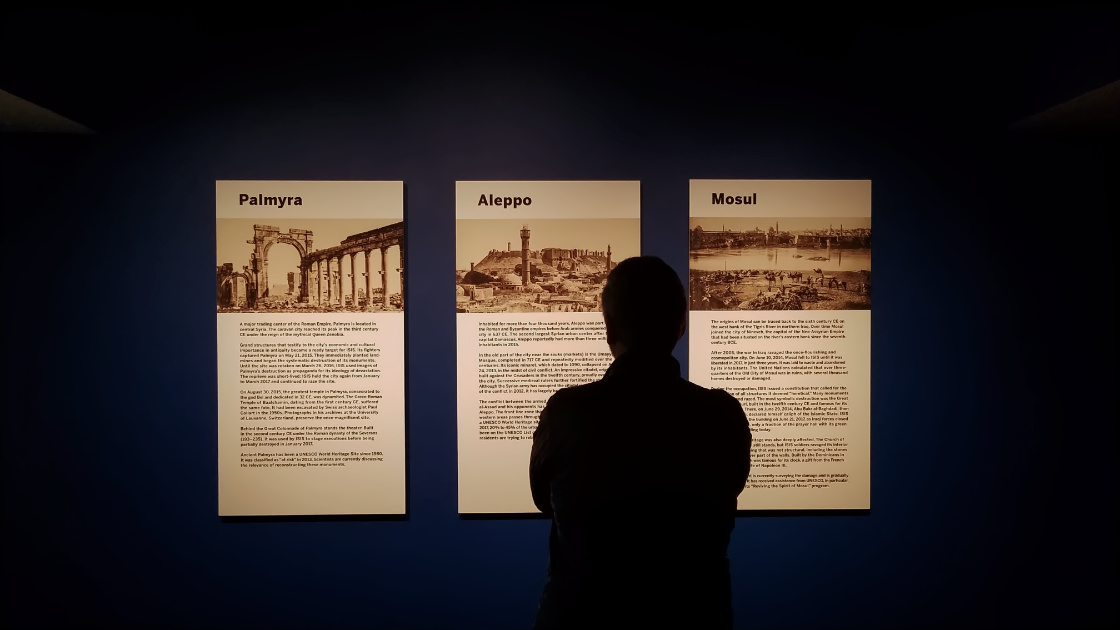

Buried deep in a sub-basement of the Smithsonian's National Museum of Asian Art, Age-Old Cities invites visitors to enter lost archaeological spaces. While the imagery of subterranean galleries may conjure ideas of excavation, no such unearthing happens as visitors explore the gallery's ruins. The exhibition's relics can no longer be recovered as they no longer exist. Age-Old Cities offers only virtual reconstructions of antiquities lost to the destruction brought by Assad, Daesh and other warring factions. Age-Old Cities contains no concrete artefacts, instead relying on projections of Palmyra, Aleppo and Mosul to capture the majesty of what once was and convey the immediacy of the crisis.A,1 The exhibition bolsters its virtual architectures with interviews and documentaries that ground the 3D models in the unsavory reality that has led to their creation.B While the ruins seen are not real per se, the cause of their virtualizing very much is.

Washington is neither the first nor last stop as Age-Old Cities travels the world in ways its relics never could. A half-hearted silver lining appears: through their destruction, the architectures have become liberated from any one site. The exhibition premiered at the Institut de Monde Arabe in Paris in 2018 and has since manifested in Germany, Saudi Arabia and Canada among others. While these ancient cities have long laid claim to sitting at the crossroads of civilizations, the nexus of East and West, their architecture remained tied to their Mesopotamian location.C Their virtualization as such provides these global heritage sites with previously unobtainable access to the globe. Such dissemination of ancient relics often proves fraught with colonial 'safekeeping',2 but Age-Old Cities pursues precisely the divestment that international viewing provides. Since no one wants to travel there, the monuments, or what is not left of them, travel here, but in reality they are not anywhere any longer. Their have become martyrs.

Alas, the space of the ruins does not resonate. Other iterations of the exhibition included virtual reality headsets,3 a noticeable absence in the Smithsonian's rendition, which certainly provides a somewhat more tangible experience than large-format projections. Rows of heavy-duty projectors cast the locations onto lengths of flat, white wall. The ruins are never entered; they are only viewed. The closest experience visitors have to occupying the spaces shown comes when they stand close enough that their peripheral vision falls within the extents of the projection. Even then, the illusion fades as no singular experiential presence exists for more than a few seconds. The camera switches between walkthroughs and aerial swoops.D In some cases this is necessary — one understands the magnitude of the decimation in Aleppo when flying over its bombed fabric — but in other it removes the reality of the ruin. The entire experience holds the viewer at arm's length from what could easily become a virtual visit to lost wonders of the world; the exhibition constantly reminds viewers that what they see no longer is. The reconstructed elements that have been dutifully digitally crafted remain ghosted over the reality of the 3D scans. As the renderings shuffle through their immense-but-not-immersive panoramas, secondary projections on side walls show historical images of the monuments in tandem.E Many of these images have been altered so that they too reflect the unoccupiability of these lost spaces. Black and white photographs of souks become vignettes of the life they once held through an augmented Ken Burns effect where the images pan with parallax.F The effect is eerie and unsettling; the dead has been brought back to life. Age-Old Cities follows through on its claim to recreate lost wonders for its viewers, but its focus ignores the wonders in favor of the lost.

As a Syrian refugee points out in an early entry of the exhibition's visitor log, Age-Old Cities is frustratingly apolitical. The ruins are everywhere, but where, or who, are the ruiners? In the interviews and documentaries, there is at most a cursory mention of 'jihadists' as the culprits. All blame falls to Daesh. The exhibition either presumes the visitor already knows the crucial nuances of the crisis, or has decided that they do not matter. The aforementioned comment takes this as a form of Assad apologism, but the benefit of the doubt leads to a more optimistic conclusion. These monuments are lost. They will not be back — or if they are, it will be as a 'Disneyland' version of themselves, as an interviewed archaeologist puts it — but their loss need not be in vain. The global status of these monuments unlocks doors across the world. Rather than show architecture, they show devastation. The destruction of buildings provides a repository for the plight of their surrounding peoples. The Romanticized ruins and times of yore push the visitor's sense of reality toward an evanescent utopia. When that crumbles, the hurt magnifies into an unbearable travesty on a personal level.G The exhibit remains apolitical because it wishes to convey the gravity of its message to any audience, regardless of their affiliations in the messy Syrian situation or their misgivings about refugees. Through virtual ruins, the actual rises.

# Date [Return to] Title

500+ Ongoing Essays

550 May 2023 Platform Gamification

504 December 2022 On the Grid

518 December 2022 A Suspended Moment

A–Z Ongoing Glossary

G September 2022 – as in Girder

F May 2022 – as in Formal

* April 2022 – Key

E February 2022 – as in Entablature

D November 2021 – as in Duck

C August 2021 – as in Czarchitect

B June 2021 – as in Balustrade

A April 2021 – as in Aalto

0–15 December 2020 Journal

15 November 2020 Practice (in Theory)

14 October 2020 Alternative Narratives beyond Angkor

13 September 2020 Urban Preservation in Cuba

12e August 2020 Conversation on Copley Square: Summations

12d July 2020 Conversation on Copley Square: Conceptions

12c June 2020 Conversation on Copley Square: Reflections

12b June 2020 Conversation on Copley Square: Nonfictions

12a May 2020 Conversation on Copley Square: Foundations

11 May 2020 Out of OFFICE

10 March 2020 Hudson Yards from the High Line

9 March 2020 Metastructures

8 February 2020 Form, Program and Movements

7 February 2020 Life in the Ruins of Ruins

6 January 2020 The Urban Improvise

5 January 2020 Having Learned from Las Vegas, or Moving past Macau

4 December 2019 A Retrospective on the Decade's Spaces

3 December 2019 The Captive Global City

2 November 2019 Temporal Layers in Archaeological Space

1 November 2019 Contemporary Art Museums as Sculptures in the Field

0 Undated Manifesto: A Loose Architecture

© 2019 – 2023 Win Overholser

Comments

Loading comments...

Powered by HTML Comment Box.