An architect alone cannot conceive a great building. The architect orchestrates, meaning that only with great players and a great venue can they give form to a great work. In the lead-up to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Kenzo Tange, Yoshikatsu Tsuboi,A Uichi Inoue, Koji Kamiya, Mamoru Kawaguchi, Kaichi Negishi, and countless others in postwar Japan suspended a moment for the ages in the sweeping embrace of Yoyogi National Gymnasium and its Annex building.

This essay explores the components that imbued Yoyogi National Gymnasium with the potent, tapped potential of becoming an architectural icon. The first section unpacks before design even begins as the circumstances that the building arrives in set a dramatic scene: an embattled historical site, a second chance to forge an international identity, and very little time to do it. From there, the second section elaborates on the established collaborative efforts of Tange and Tsuboi, which led them to realize Yoyogi's elegant design through a friction between the architecture and structure where neither took over the other. The third section discusses the construction of the Gymnasium where the challenge of building Tange's particular form became apparent, and Tsuboi's apprentice, Kawaguchi, proposed an hybrid structural solution that achieved it. In short it is the confluence of these forces that brought about the Gymnasium's success. Tange is by all means a talented architect, but the success of Yoyogi is not his alone. It is Tsuboi's. It is Kawaguchi's. But primarily, it is Japan's.

Yoyogi began its modern life in the late 19th century during the societal restructurings of the Meiji period. This half-century leading up to World War I saw a number of changes across Japan as the nation modernized to avoid the impending threat of Western colonization. Until then Yoyogi had housed daimyos (feudal lords) and their vassal samurai. Under Emperor Meiji this archaic way could not continue, and the lands were confiscated from the daimyos and turned into new districts. Over the last decades of the 19th century, the site saw a variety of uses under its new Imperial ownership before it became the Yoyogi National Parade Grounds in 1909.1 Emperor Meiji and his wife both passed in the following five years, and a Shinto shrine dedicated to his and his wife's spirits stands to this day on the northern edge of Yoyogi.2

From Emperor Meiji's death through World War II, Yoyogi was a popular destination for Tokyoites who wished to see displays of Japan's military might. Emperor Hirohito, leader of Imperial Japan during WWII, celebrated his thirty-second birthday at Yoyogi National Parade Grounds in 1933, leading over 15,000 soldiers on parade.B After the Japanese defeat in 1945, nationalist locations like Yoyogi became subject to scrutiny by foreign powers, and on September 8 of that year, the United States Army began an occupation of Yoyogi that would last almost twenty years. Rebranding the area as Washington Heights, the U.S. military constructed "hundreds of residences, elementary schools, churches, and more."3 In less than a century, Yoyogi had transformed from feudal farmlands to nationalist parade grounds to American suburbs.

In 1936, before the war, the International Olympic Committee awarded Tokyo the rights to host the 1940 games. Japan eventually forfeited their hosting rights in 1938 with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, which began Japan's involvement in WWII.4 The steel needed to construct the new stadiums simply could not be sourced with the ongoing war efforts. During that initial hosting period, some members of the Tokyo Olympic Organizing Committee had recommended Yoyogi as a potential site for new stadium construction, but this proposal was shot down as "the idea of squandering the imperial army's parade ground for mere sports" ran counter to the nation's rampant militarism.5 In the occupied, post-war context, the idea became more appealing to government officials. The idea of hosting the Olympics, too, was recontextualized. No longer would it entail the nationalist pride of pre-war Japan. Instead, hosting the games would serve to reintroduce the new, post-war Japan as a committed member of the international community. Although bureaucracies around Tokyo debated on where to site the new stadiums, eventually the appeal of Yoyogi — and its concomitant removal of the blight of American occupation from Tokyo's center — won out as the central venue.6 Not only did the site have space for the new stadium construction, but the deal brokered with the American military provided a pre-built Olympic Village in the suburbia of Washington Heights.C Almost thirty years after Tokyo lost its Olympic bid, and over twenty since Japan damaged its international reputation, a new dawn emerged in the Land of the Rising Sun.

With the location set, a new challenge arose. The Americans returned portions of Washington Heights to the Japanese on November 30, 1962, but builders would not be able to break ground until February 1963.7 The games would begin less than 20 months later on October 10, 1964. Construction supervisor Kaichi Negishi recalls that "although the minimum construction period was 22 months, it was shortened to 18 months … in order to make it in time for the Olympic training."8 There would be no time to host a design competition and complete construction. In fact, many elements of the design would only be resolved during construction.

Luckily the debates over who would design the new stadium happened concurrently with those on where to site the buildings, so the tight timeline did not suffer further. Chairperson Hideto Kishida led a committee composed of members of the Ministries of Education and Construction, who met throughout November 1961 to select an architect. They finally agreed upon a discretionary contract for the preliminary design of the stadiums, naming three esteemed Japanese building designers: architect Kenzo Tange, structural engineer Yoshikatsu Tsuboi, and MEP engineer Uichi Inoue. After the preliminary designs were reviewed and published in May 1962, the committee decided to keep the initial team on for construction documentation, which the team would complete in September 1962.9 This whirlwind of activity would not have been possible without the talented individuals who already had familiarity with each other's processes. Tange and Tsuboi's team proved to be a perfect fit for this time-crunched job.

Though by far the largest and most structurally ambitious project Tange and Tsuboi undertook together, Yoyogi National Gymnasium came along deep into their collaborative years. Their relationship began over a decade earlier in 1952. Tsuboi recalls: "One day, early in the morning, Tange visited me at my house and asked me enthusiastically to collaborate with him on the structural design of Hiroshima Children's Library. He even offered half of the design fee."10 Tange's eagerness to work with Tsuboi proliferated in numerous projects over the years, including the Ehime Prefectural Citizens' Hall in 1953, the Shizuoka Convention Hall in 1957, and St. Mary's Cathedral in 1964 — whose design occurred alongside Yoyogi National Gymnasium's. Unlike Yoyogi's suspended roof, however, these Tange-Tsuboi collaborations fall into the realm of compressive shell structures, a subject that Tsuboi researched extensively.11 The Gymnasium would be much more challenging structurally as shell theory's inflexibility came up against the flexibility inherent to suspended structures. Tsuboi would bring on his apprentice, Mamoru Kawaguchi, who would go on to develop a plethora of suspension-based structural systems over his career, to stretch the limits of what could be achieved.12

The roof of Yoyogi National Gymnasium is not rational, nor does it readily rationalize. Tange envisioned a particular type of curve — one that was neither a catenary nor any other simple, mathematically reducible shape. Instead the roof seeks something less deterministic in its origin, yet more transcendent in its result. Kawaguchi notes that "although Tange explained why and how he applied the suspension roof system to his Yoyogi Stadiums, he never talked explicitly about what sort of architectural forms he pursued in his design. …[He writes] of his design criteria only in rationalist terms, but the outcome of his design produces a strong atmosphere of local tradition."13 The form is distinctly Japanese.D He achieves this ethereal outcome through a number of details, none of which entirely capture the overall effect: the chigi-like notches where the cables attach to the masts, the upturned eaves, the swirling tomoe-like shape of the plan.14 Regardless, Tange drew a form without compromise, which meant Tsuboi had to make it stand whether or not gravity would assist its shape. Fortunately Tsuboi agreed that "the purpose of a building is to serve the local society in which it exists," and that its "aesthetic value … should be examined taking into account the tradition and history of the locality."15 The common link of Japanese tradition and identity, unspoken in Tange's case and generalized in Tsuboi's, served as common ground during the design process, but their collaboration relied on much more.

Both Tange and Tsuboi vocalize their thoughts on the collaborative process between architect and structural engineer.E Tange bemoans the trite belief "that structural engineers act either as tyrants or servants to architects," and continues by discussing his collaboration with Tsuboi: "I do not think we have been tyrants or servants to each other. Nonetheless, I have always felt some friction during our collaborations. This might have been due to our unfamiliarity with the novel space to which we tried to give a form."16 Tange welcomes the reciprocal role of the engineer, one that balances the architect, but that still forces compromise between the two as they develop a project. Unsurprisingly Tsuboi echoes this sentiment, writing that "it is the best for structural and architectural design works to proceed simultaneously with mutual cooperation. Structural engineers should refrain from discouraging architects… . Architects and engineers should have a mental attitude of cooperative creation." Tsuboi goes even further, however, reiterating "that architectural beauty exists at a slight deviation from structural perfection."17 The friction that Tange mentions reemerges, rubbing between architectural fancy and structural rationality to produce beauty. As Tsuboi famously quipped: "A structure's beauty can be found near its rationality."18

Though vocal about his collaborative process, Tange says nothing on how he thought about the formal qualities of the Gymnasium. He offers a few insights on many elements of the design, but none reveal the particularity of the roof's form. "It was relatively early on that a 'suspension structure' was selected," Tange writes on the creation of the expanse needed for the Gymnasium, and that he felt an "anxiety that such a huge space would become inhumane."19 The Gymnasium needed to be a dynamic space where one could feel the international unity of the Olympics, and creating this space for an audience of everyone drove Tange's design. He claims to achieve its cohesion and humanity under the drape of the catenary ceiling, but he remains reticent on the fact that his ceiling does not follow a true catenary curve. He goes into more detail about other architectural decisions used to achieve this outcome, such as the desire to allow visitors to see the entirety of the space from anywhere inside, and the need to connect the Olympic complex to existing civic nodes through grand promenades.20 In fact, Tange expressed regret that he could not create greater interconnectivity through pedestrian bridges and parking due to the limited scope of the site and the already large footprint of the building.21 On its urban location, Tange does hint at the Japanese undertones of his universal architecture: the Gymnasium shares an important north-south axial alignment with Meiji Jingu, the aforementioned shrine to the spirit of the late Emperor Meiji and his wife.F

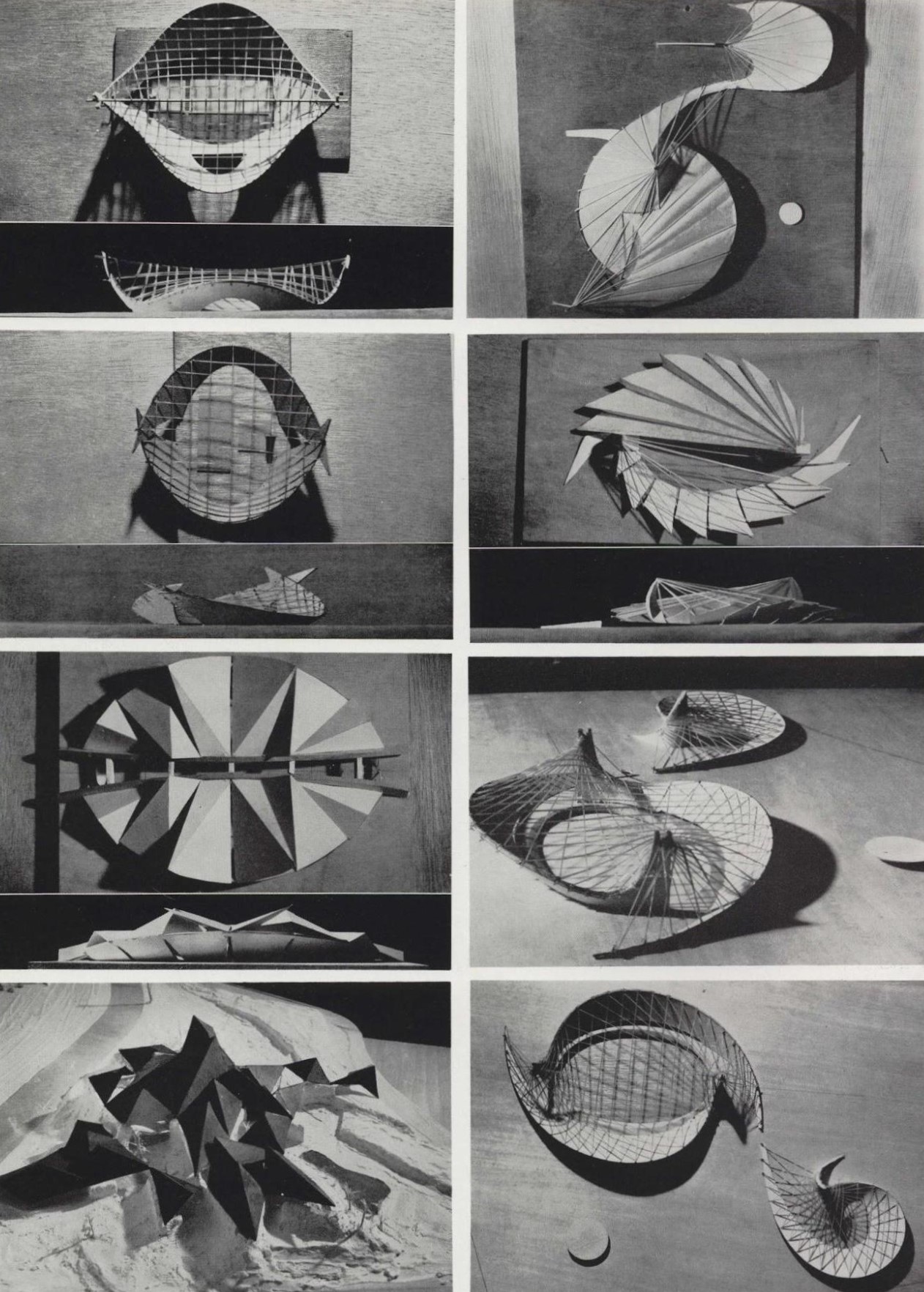

Where Tange keeps quiet about his Japanese form, his second-in-command, Koji Kamiya, offers more details in his contribution to the project's final report. Kamiya outlines his exploration of the formal possibilities of suspended structures through iterative model-making,G including a number of seemingly non-tensile origami models. Along with Tange's desire to create a gigantic-yet-humane space, this process led to the split between the Gymnasium building, housing the pools, and its Annex, housing the basketball court. The form came in part from the need to balance the two buildings, and to create a holistic image between them.22 The study models nevertheless leave off before the final form takes its complete shape. Only during construction would it fully materialize.

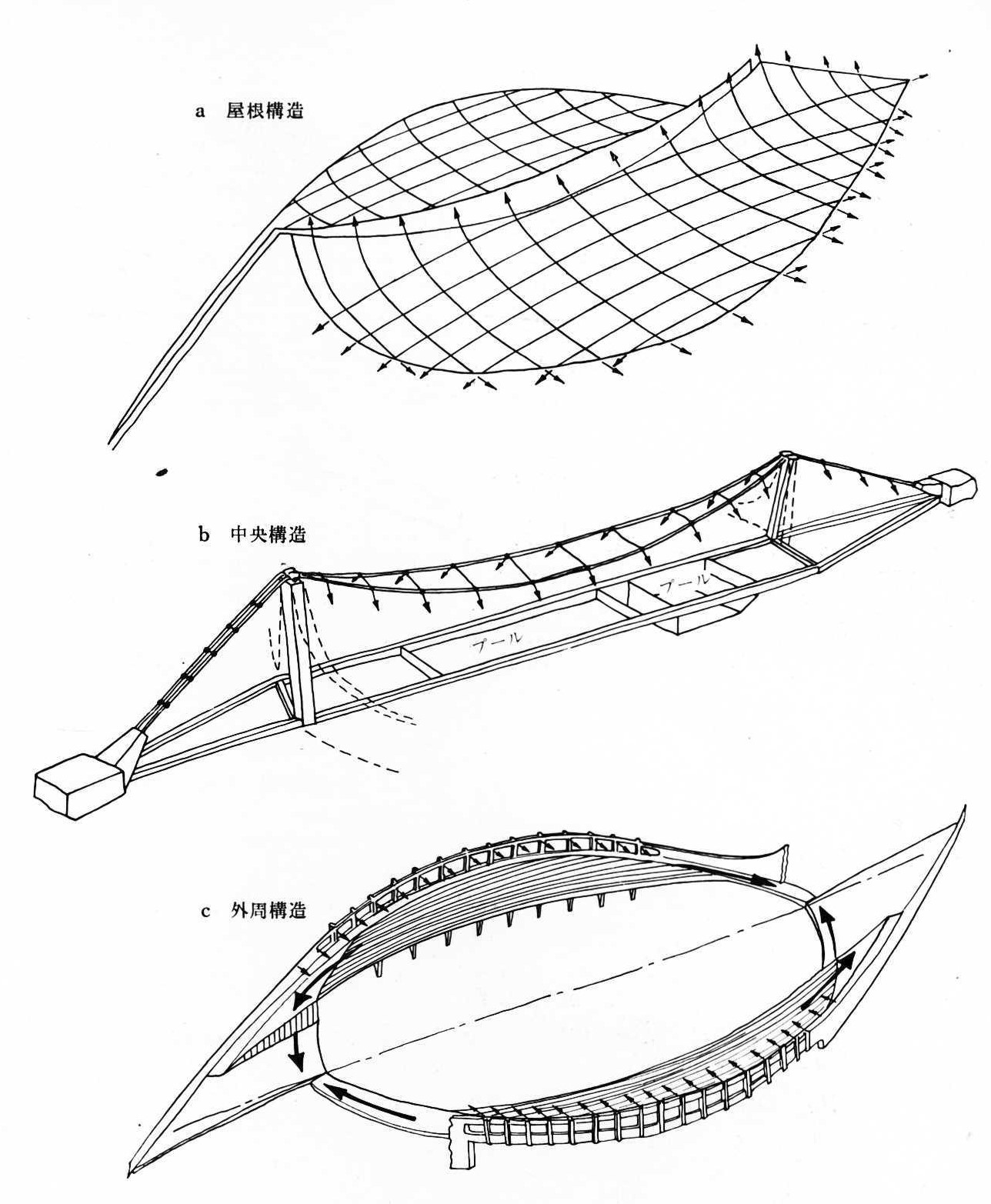

The basic structure of the building can be summarized in three parts:H i) a non-catenary, suspended roof, whose manifestation will be the primary focus of this section; ii) a suspension bridge-like pair of cables that follow a catenary between two vertical masts; iii) two offset, elliptical, reinforced concrete grandstand-ramps that gently lift off the ground, mirrored asymmetrically.23 These three forms impact each other in complex three-dimensional ways. The central cables are pulled apart in the middle by the hanging roofs, creating a large central skylight. They also kink at each mast, using the sweeping grandstands as buttresses, and creating an awning from the roof at the entry points at either end of the building. The grandstands appear to lift off the ground, reined back by the suspended roof in a polite curtsy. The shape of the roof would be complex enough if only generated from the dynamic curves of the cables and the grandstands, but Tange's particularities come into play as well. Furthermore, the suspended nature of the roof requires built-in wiggle room to accommodate undulations from wind and snow loads. The roof's structure could be flexible, but its formal qualities were anything but. Tange's team had at this point arrived at the roof's final form, and its construction needed to capture this intent.

When the preliminary designs were published in May 1962, the roof's form was almost solidified. Its revisions during the working drawing phase would still leave a "huge gap between this image and reality… . For [the design team], it was literally a time full of tension and suspense."24 While Kamiya's turn of phrase is playful, it misleads. After the roof's tumultuous construction, Tsuboi can clarify that the roof is "a surface which could not be achieved by a pure tension structure. The problem was solved by a group of hanging members with bending stiffness being hinged at one or two intermediate points of spans. The above idea … showed how important it was for us to foresee the behavior of a structure before we start calculating it."25 Herein lies the great issue of the Gymnasium's roof: only during construction would the design team figure out how to build the roof to look as intended within feasible means. Perhaps Kamiya's pun would be more apt if he lamented that the stress had bent him out of shape.

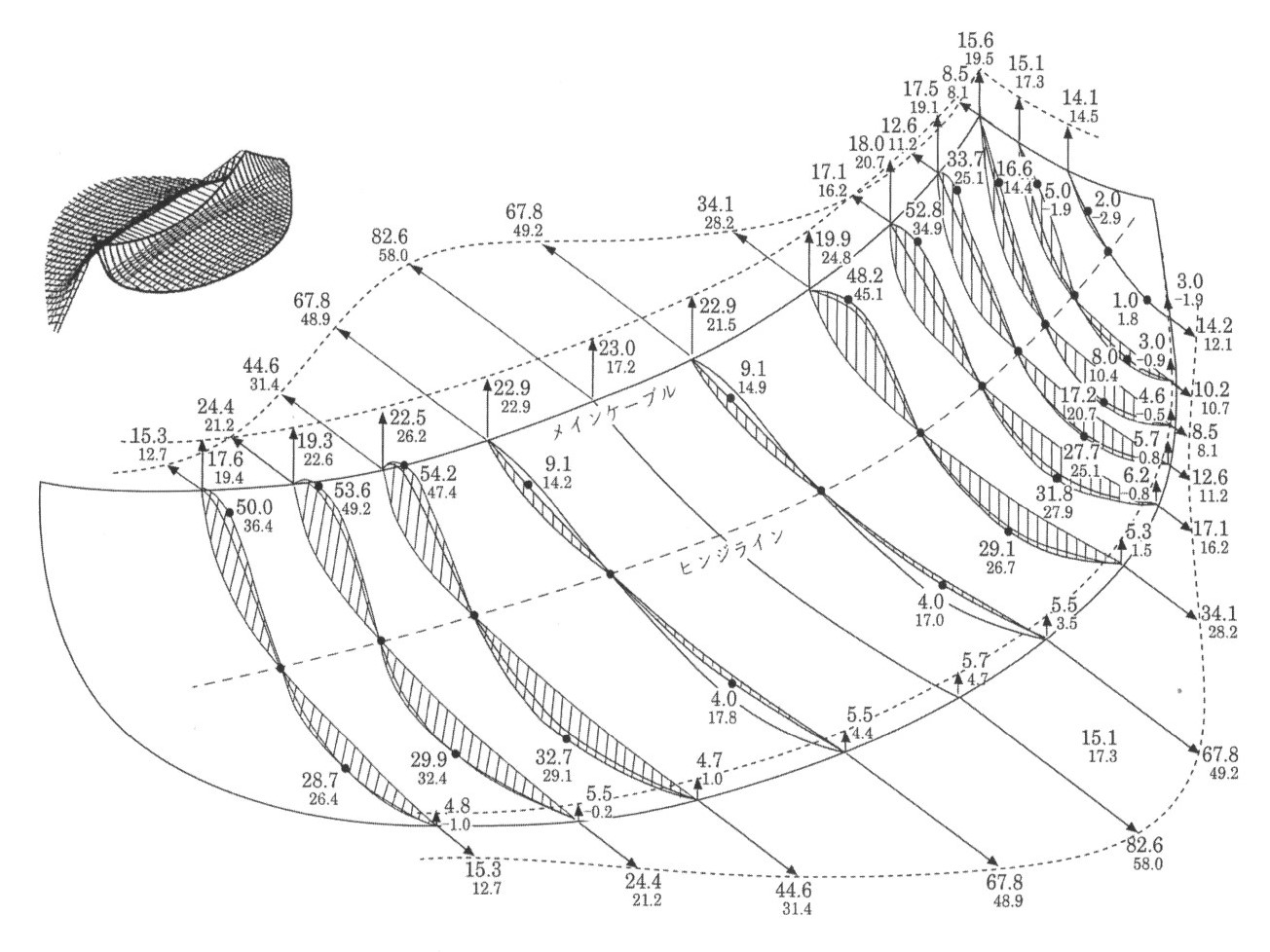

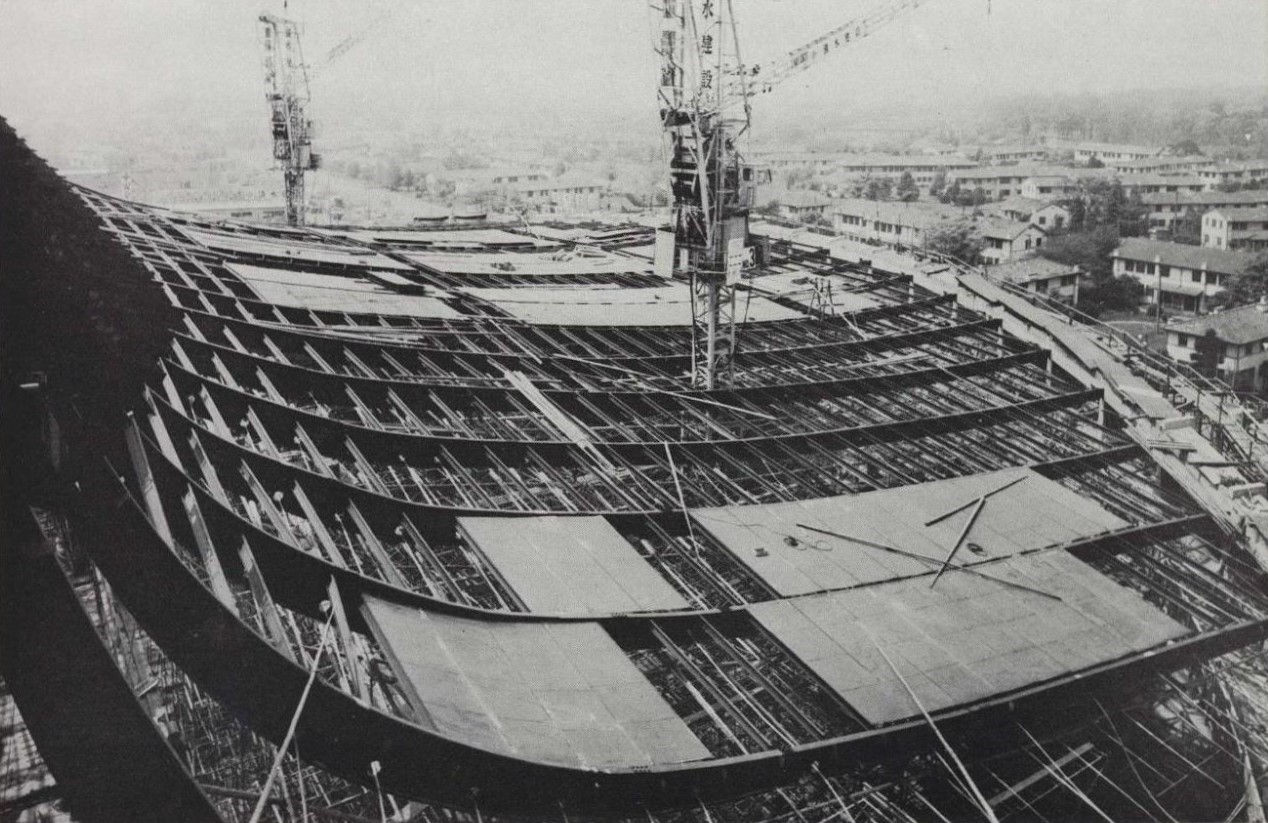

The original plan on how to construct the roof involved a hanging net with stiffening ribs placed on top in the form of tall I-beams. On site it became clear this would not work as intended. On a formal level, the hanging net would not match the drawings near the central spine, where it deviated farthest from a catenary curve; from a performance standpoint, the desired, vertical-only movement of the stiffening ribs under wind loads would be at odds with the free-flowing net on which they would rest; and from a construction standpoint, the nodes where the stiffening ribs would tie into the suspension ropes would be incredibly difficult to install.26 Structural experiments during the design process had already shown that other, more conventional suspended systems would not adequately capture the complex curve of the roof.27 Kawaguchi suggested switching from the original system to a structure made almost entirely of steel beams. As construction was ongoing, the team raced to work through Kawaguchi's proposal. "We developed a suspension roof surface consisting of hanging members with some bending rigidities," writes Kawaguchi after the fact, "then we had to establish the fundamental equations for the semi-rigid hanging system."28 Kawaguchi knew that no other suspended structural system could capture Tange's curve, so he had no choice but to develop and calculate an entirely new one in the limited time left before the games began.

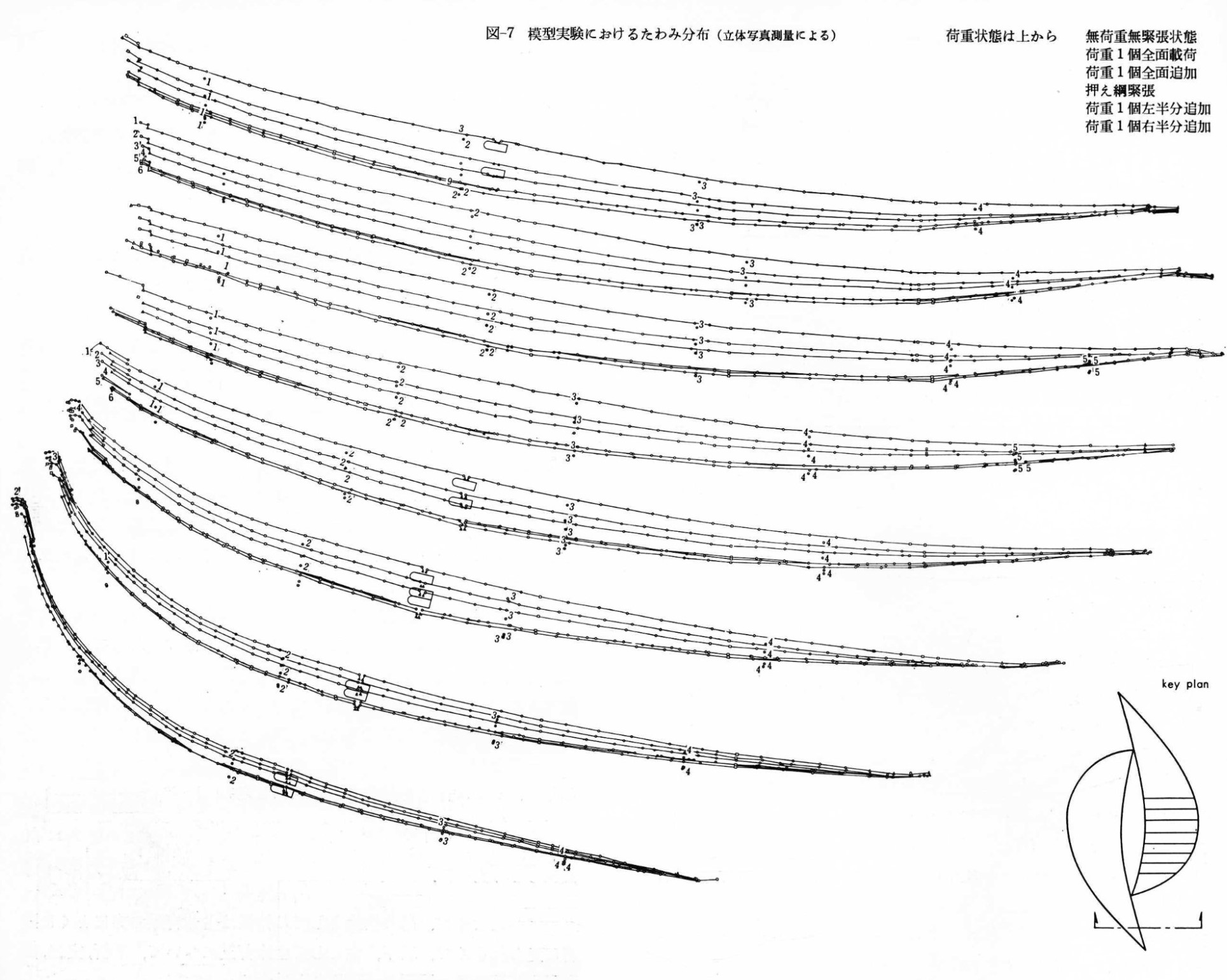

By switching to steel beams only, the roof became substantially less dynamic due to the inelasticity of steel compared to the original suspension cables. While this resolved some stability issues, it meant the construction process would need further revision. Previous calculations had shown that the two central roof cables along the spine of the building would droop approximately two meters as they took on the load of the roof as it was constructed. The steel beams would be twenty-four centimeters too short to accommodate this change while still maintaining the desired shape. Kawaguchi devised another solution, splitting the beams in two with a pin-joint at the point along their span where they had zero bending moment.I In this setup, the beams could be installed between the cables and the perimeter of the building as nearly straight lines, dropping into their final curved forms once the scaffolding came out from under them.29 By now well-versed in the dynamic shifts that suspended structures undertake, Kawaguchi used the roof's inherent flexibility to install it.J However, splitting the up to eighty meter long steel beams with a hinge did not resolve all the issues. The beams would need to be specially manufactured to include the necessary three-dimensional curve they would follow, and even divided in two they were still much too long to be transported to site. Nippon Kokan, the steelmaking and shipbuilding company who would manufacture the beams, remained skeptical of the obvious solution: welding multiple segments together. If one weld were to give, the whole suspended roof would collapse. After much debate, "someone around Mr. Tange persuaded Nippon Kokan … and eventually got the OK. The three-dimensionally bent steel beams were divided into seven parts."30 Finally, the biggest change to the project during construction — one fundamental to the undergirding idea of the project and its unique form — was resolved.31

Despite how integral the roof is to the overall building — its iconic exterior and embracing interior — it remained intangible until the moment it needed to be made. To this day its Japanese qualities are still somewhat inarticulable, but like Yoyogi National Gymnasium as a whole, it captures a particular moment and the energy it contains — both literally in its bending moments and metaphorically in its rushed-yet-refined resolution.K It is a roof that defies simplification because it does not arise from structural rationality. It is a hybrid of history and modernity, of the local and the international, of architecture and structure. "Kawaguchi is not dogmatic, and he combined cables with beams to create an altogether new shape. Nevertheless, I think most architects and engineers — regardless of style or approach — would agree that the space thus created under the roof is beautiful."32

Yoyogi National Gymnasium is a great work of architecture, but Kenzo Tange cannot claim its success for himself. Its excellence arises from its circumstances, its site, its history, and how everyone involved channeled those particularities into something greater than any one of them. Like Emperor Meiji's shrine to the north, Yoyogi National Gymnasium represents a spirit: the spirit of postwar Japan, forever suspended in its roof.

# Date [Return to] Title

500+ Ongoing Essays

550 May 2023 Platform Gamification

504 December 2022 On the Grid

518 December 2022 A Suspended Moment

A–Z Ongoing Glossary

G September 2022 – as in Girder

F May 2022 – as in Formal

* April 2022 – Key

E February 2022 – as in Entablature

D November 2021 – as in Duck

C August 2021 – as in Czarchitect

B June 2021 – as in Balustrade

A April 2021 – as in Aalto

0–15 December 2020 Journal

15 November 2020 Practice (in Theory)

14 October 2020 Alternative Narratives beyond Angkor

13 September 2020 Urban Preservation in Cuba

12e August 2020 Conversation on Copley Square: Summations

12d July 2020 Conversation on Copley Square: Conceptions

12c June 2020 Conversation on Copley Square: Reflections

12b June 2020 Conversation on Copley Square: Nonfictions

12a May 2020 Conversation on Copley Square: Foundations

11 May 2020 Out of OFFICE

10 March 2020 Hudson Yards from the High Line

9 March 2020 Metastructures

8 February 2020 Form, Program and Movements

7 February 2020 Life in the Ruins of Ruins

6 January 2020 The Urban Improvise

5 January 2020 Having Learned from Las Vegas, or Moving past Macau

4 December 2019 A Retrospective on the Decade's Spaces

3 December 2019 The Captive Global City

2 November 2019 Temporal Layers in Archaeological Space

1 November 2019 Contemporary Art Museums as Sculptures in the Field

0 Undated Manifesto: A Loose Architecture

© 2019 – 2023 Win Overholser

Comments

Loading comments...

Powered by HTML Comment Box.